- Home

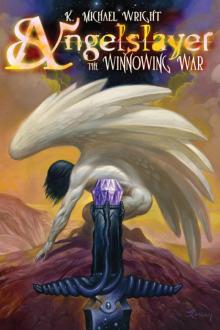

- K. Michael Wright

Angelslayer: The Winnowing War

Angelslayer: The Winnowing War Read online

DEDICATION:

For Buffy who always believed.

Published 2008 by Medallion Press, Inc.

The MEDALLION PRESS LOGO is a registered trademark of Medallion Press, Inc.

Copyright © 2008 by K. Michael Wright

Cover Illustration by Jeff Easley

Cover Design by Adam Mock

Book Design by James Tampa

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

There are numerous Cherokee Counties throughout the South, none of which are represented by the fictional locale in this book. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictionally. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Printed in the United States of America

Typeset in Adobe Jenson Pro

Title font set in Sloth and Parseltongue

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wright, K. Michael.

Angelslayer : the winnowing war / K. Michael Wright.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-933836-53-9 (alk. paper)

1. Angels–Fiction. 2. Spiritual warfare–Fiction. I. Title.

PS3623.R554A84 2008

813'.6–dc22

2008018228

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Many thanks to Carrie Wright whose help as an editor and talent as a writer helped bring Angelslayer to life.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter-Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

* * *

There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men, which were of old, men of renown.

King James Version of Genesis 6:4

Chapter One

Darke

An isle in the Southern Sea of Etlantis Thirty years before Aeon’s End, the first apocalypse of Earth

The sky was a slate gray when Darke’s ship pulled into the island’s cove. The waters of the lagoon could have been inked. Darke, the corsair, was a lean figure atop the forecastle; his black mantle flared in night’s wind; his hair curled about the shoulders of his leather jerkin. His men were gathered. They were men hard of the sea.

At the forward ports, archers crouched, waiting. Amidships, the mighty crossbow, with its fifty-stone draw, was armed with an oaken bolt fitted with a heavy, rusted iron tip. At the cutwater strakes, the siphon jets of the flame throwers curled their fire breath against the prow.

In the lagoon across from them, an Etlantian galley rested. Rather, it once had been an Etlantian galley. Etlantian ships were brightly painted—red and blue, green and white. Solid plates of oraculum, the Etlantians’ silver-red metal, always wreathed the top strakes; in the sun they could reflect the color of bright blood, but this ship was a brigand, with time eating slowly at the hull and sailcloth.

Darke’s own ship was black and waxen. Its sails were designed light but strong, a sacred ashen color that had allowed the night runners of Captain Darke to cut the sea like shadow. Darke’s ship could appear from nowhere—always at Darke’s chosen time, always at Darke’s chosen place, always with speed, and sometimes with such stealth that many an Etlantian had died in the sea never knowing he had been brought down by the Shadow Hawk, the last of the Tarshians—the giant killers, the raiders of Ishtar’s horned moon.

However, this night Darke had not come for battle.

Storan stood beside his captain as the warship drew quietly into the deep of the lagoon. Storan was the helmsman. He had been with Darke from their youth, from the beginning when blue blood coursed through their veins, and they could as easily have sailed the stars as the sea. Storan was a bearlike figure with deep, dark eyes inset like a bull’s beneath thorny brows. He had ill-kept, graying hair. His axe, a yawning blade well quenched of blood, was always at the ready, sheathed in a woven leather belt lashed against his muscled thigh.

There had been a time in memory’s reach when Storan and Darke had sailed as lords of all Tarshish, the emerald cities of the Tarshians, but Etlantis had destroyed the cities of the Tarshians, laid them waste one by one, and now any Tarshians alive were raiders, hidden among the isles of the sea. They were becoming few, like carnivores that once ruled but now were being hunted for sport to extinction.

The world had changed since Darke first sailed. Most of all, the Etlantians, the sons of the angels, had changed. This last generation was like no other. Giants, some stood seven foot and more. Some were barely recognizable as human, and so they were called Nephilim, spawn of the fallen. Holy blood ran in their veins, but unholy flesh twisted them, drawing them into aeon’s breath, the folding of time, the ending of all things.

The Etlantian galley in the lagoon was a large ship of the line. She had once been prime, a three-tiered craft, one-hundred oared, with four masts and a spar like a great spear, sheathed in oraculum that arched over a bull’s-head ram. On her main deck were three catapults. Her sides were lashed with grappling planks, and bolt launchers ringed her bow ports like teeth. Her fire throwers were both fore and aft, but they were unlit, dripping an oily drool over the cutwater timbers.

She lay in the harbor like a fat-bellied whore, and yet, even then, her majesty still lingered in a shadow. This was not the ship of a Nephilim, of an angel’s son, or even of an Etlantian prince—those born to the angels in olden times, who were often still honorable. This ship belonged to none of those. Though no emblems adorned her and no colors fl

ew from her top masts, Darke could trust his instincts: this was the ship, not just of any angel but of a Named—Satariel, the lord of the Melachim, the sixth choir of the third star. This was a Watcher’s ship, the ship of a high-blood angel. He was here somewhere, waiting, just as he had promised. Darke raised his hand.

“Lay back the oars!” Storan echoed the command.

The oars lifted in a single, powerful sweep and whined as they eased back against the oarlocks into their beds. Silence. Timber moaned as Darke’s low, sleek warship circled slowly in idle current, keeping its distance from the Etlantian. Darke’s ship looked like a black bird resting in the night.

Had he spotted Satariel’s ship at sea, Darke would not have been sure whether to attack or to raise colors. It was said that Satariel had sunk more Etlantian timber than even he, and as evidence, the oraculum ram of the angel’s ship was scarred like a well-used blade.

Storan, the muscled helmsman, studied the ship skeptically. “The bitch is at anchor, her oars in lock. If we struck her now, we could split her like a crab.”

“I have come in truce,” Darke said.

“You know as well as I that we are nothing but bait, Captain.” Storan spat over the side. “So where is he? Where is this unholy bastard?”

Darke studied the lagoon. Storan was right; they were unprotected here. If this were a trap, the lagoon offered no protection. If Etlantian warships were to close on the mouth of the lagoon, death would follow in short breath.

“Drop anchor,” Darke said quietly.

Storan shifted uneasily before giving the order. “Do not much like anchoring out here with our asses bared in moonlight like painted whores.”

“Storan, if he is who he claims, we would be as dead as stone if he desired. So far, he’s kept his word, which means he needs us for something. We’ve come this far; we may as well learn his purpose. You think?”

“You would rather not know what I think of all this, Captain.” He turned. “Let out the stone!”

The anchor chain rumbled as the weighting stone splashed into the quiet waters.

There were times Darke could sense things, times he could feel a merchantman before she ever pulled onto the horizon. He could pick his way through the coral reefs of islands as if he knew their skin. And weeks ago, when a river ship had hailed alongside and its captain, an aged, withered giant—an Etlantian—had given him the scroll, something seemed to promise that it was no trick. The scroll was aged papyrus, and its edges had been dipped in blood. Darke broke the waxen seal with its bull’s-horn signet. It had been an invitation, more likely a trap, but either way, it had fired his curiosity. Because of it, Darke had sailed to this island to see the face of an angel. He wanted to gaze on a being who had been roaming Earth since the dawn of man, a being whose eyes had withstood God’s fire. Darke almost didn’t care the cost. “Where is it we are to meet him?” Storan asked.

Darke searched a moment and then pointed toward the dim light of a tent, beached to the lee of the Etlantian galley. Although barely visible, Darke had found it easily.

Darke’s mother had laid a balm of nightshade and galbanum on his eyelids before the umbilical cord had been cut, and thus she named him Darke and promised vengeance of the night.

“There could be fifty men in those trees, Captain,” Storan grizzled. “You said he would meet in the open. I name that alone breach of word. I say we try to kill him now and mark our names in the list of the damned.”

“He is a dark angel of the holy choir; he might prove difficult to kill, Storan.”

“I do not indulge beliefs of angels of light or of dark, nor do I care for choirs. I want a song; then, I will find me a whore with a sweet voice in a tavern somewhere.”

“Not that kind of choir, I fear. This angel has slaughtered enough innocent blood to fill this lagoon.” Darke turned and spoke quietly. “Bring me Danwyar.” Calls went out for Danwyar.

Darke searched his men. He needed a shore party, a small one. Anxious, Taran stood with his hand over the hilt of the double-edged iron he had taken off a Pelegasian breached at high sea. Taran was Darke’s brother, though younger by twenty-two years, something of a mistake of birth on his mother’s behalf. Taran was only ten and nine. He’d be a fine warrior someday, but that day would never be reached in the light of this sun. The sun of Darke, the star of this earth, now numbered its days carefully, and though he never spoke of it to his men, Darke knew the numbers. Taran would die too soon, ever to become the slayer for whom he had been named, his great-uncle, the lord of Anguar, Taran the Red.

Still, the boy was good. More kills than his years, and that by Darke’s count alone. Who knew how many more in the scream of battle? The sword the boy had chosen was heavy and whetted with a taste for blood. Darke had seen him working it for long years now. That was not the reason Taran had been chosen; the reason was that the boy’s only chance of surviving was to learn. This was to be one of those occasions where one either lived or more likely died—but it was certain one would learn something, something of critical importance.

“Taran, prepare a longboat.”

Taran nodded and quickly dropped over the forecastle railing to begin paying out the longboat lines. Sometimes Darke wondered how he saw through the long, sandy hair so often in his eyes.

Danwyar had climbed the ladder to the forecastle and now waited silently. Danwyar was small and bald on the whole of his body from a disease that had caused his hair to fall out. If anything, it made him all the swifter. His bow and short sword moved like the tongue of a serpent, and he could see well enough to navigate by stars even though cloud cover would discourage the most seasoned pilot. He was descended of the princes of the second city of Tarshish, and his father had been Ryhall, the king of Ichnosh. Not only was he the named second of Darke, but also he was far and away the best man the captain had.

“You will take the helm, Danwyar,” Darke said. “Anything proves wrong, gut the Etlantian. Sink her.”

Danwyar nodded.

“Storan, you will come with me.”

Storan merely chuckled. “You can kiss my sweet flowery ass on that,” he said. No one could stop Storan from coming if the life of Darke, his king, was to be in danger.

“And Marsyas,” Darke said.

Marsyas was full-blood Etlantian, ugly to begin with, and standing near seven foot. A blow had once split open his face, and he had been found among the dead of battle. Not a Nephilim, he was a lesser born—a third generation born. Nephilim were firstborn only, direct descendants of an angel. But Marsyas had been born powerful, intelligent, and strong, and he had brought down ten men that battle. Darke kept his life, and Marsyas had sworn oath. It was said the children of Marsyas’s generation, the third generation of the sons of the Angel’s Isle, had fallen to the curse of Enoch such that only the meat and blood of men would quench them, but if the curse was with Marsyas, he kept his blood-taking to those who, in his own opinion, deserved to be drained. Darke always held his hand, as he would in a tight game of dice: there were bad Etlantians, but many were still good, many still men of lineage. Some of the older princes of the firstborn were of the light and so were, in Darke’s mind, many of the angels. They had to be. They had been bred pure of God’s blood; their eyes had seen God’s light. Foolish men said they had fallen for woman, for the daughters of men, but Darke would hedge his bet on that.

Marsyas, though a third-generation descendant of the angels, was one of the best comrades Darke had met on this small world. He was as loyal as Storan.

Marsyas had but half a tongue. He could speak, but seldom did. In response to Darke’s command, he only brought his big fist to his chest.

Darke was satisfied—Taran, Marsyas, and Storan—enough for a good killing, certainly enough for a chat with an angel.

In the longboat, they passed slowly beneath the stern of the angel’s Etlantian galley. Dull light filtered through thick, semiopaque windows of the cabin structure. From the deep of the lagoon, it had looked abandoned

, but now, along the top railings, figures watched them pass. They seemed to have no focus, no faces. They might have been nothing more than shadows.

Once past the Etlantian hull, the keel of Darke’s longboat hit the sand. Storan and the boy leapt out, wading through warm water, to set the shoring blocks.

The four pirates assembled on the beach. The tent, lit by braziers from within, was down the shoreline some twenty yards. Storan let his thick fingers curl about the worn haft of his axe, but he did not draw it.

Darke looked to his brother. “Taran, you stay here with the boat. Should anything happen to us, try to get back to the ship to warn the others.” Taran nodded.

Darke, Marsyas, and Storan walked slowly along the water’s edge. The only sound was that of the shallow surf. The trees and vegetation should have been humming with insects, but they were dark and silent. Near the brigantine ship and the single, unadorned tent in the sand, the foliage had begun to die. There was even a stink to it. From the corner of his eye, Darke noticed the body of a cormorant, lying on its back, its legs stiff, its head twisted full about, face into the sand. It seemed an odd sight.

Marsyas walked silently, without emotion, but the closer they got, the more nervous Storan became.

“Sweet and holy Goddess as my witness,” Storan muttered. “I do not like this, Captain. My mother would tell us to turn back now, she would. I know that to speak to you at this moment will be no more productive than to piss in the wind, but there will be no good to come of this; I promise you that. ‘Tis a bad season, this. I feel the turning in the air. We’d be coming into a storm not of this world.”

“Are you going to talk the whole night, Storan?”

“Why? Will you listen to what I say?”

As the tent of the angel became clearer in the night, what appeared to have been black canvas was instead dark red, glistening slightly from the dull torchlight within. The smell of it was certain. It was coated in blood that had not yet dried. There were fields of slaughter that held this smell, this sour, slightly metallic taste. The stakes anchoring the tent’s edges turned out to be leg bones, snapped at the kneecaps and driven into the sand. Darke would be damned if the tent had not been made wholly of the flesh and bone of men. Here and there were swatches of stiff human hair.

Angelslayer: The Winnowing War

Angelslayer: The Winnowing War